Presented by Chase Day:

What is a Donkey?

The Donkey Society of Victoria (DSV) was formed in 1972 by a small group of donkey enthusiasts. The DSV is a member of ‘The Affiliated Donkey Societies of Australia’. On a national scale, records are maintained of the parentage of each donkey registered so a pedigree of five or six generations is on record for many of the donkeys being born now.

The purpose of the Society is primarily to promote the well being of Donkeys in Australia be they wild or domesticated by:

• Encouraging the breeding of sound, quality donkeys. To do this the Society shall, in association with the other affiliates of the Affiliated Donkey Societies of Australia, maintain a Stud Book for the registration of stock.

• Providing education on the care of donkeys.

• Promoting research into all matters relating to donkeys, their health and general care.

• Encouraging and supporting the exhibition of donkeys.

• Participating in the prevention of cruelty to donkeys and co-operating with any other organisation actively engaged in preventing cruelty.

• Promoting the public image of the donkey as a useful animal as well as an engaging pet.

Most of us can picture a donkey…. It is like a horse, but smaller… usually grey in colour, with comically large ears. We might have seen them carrying holiday makers at the seaside, or in a petting zoo. They are considered stubborn or stupid and the butt of jokes. Winnie the Pooh had a depressed one as a friend. But what is a donkey?

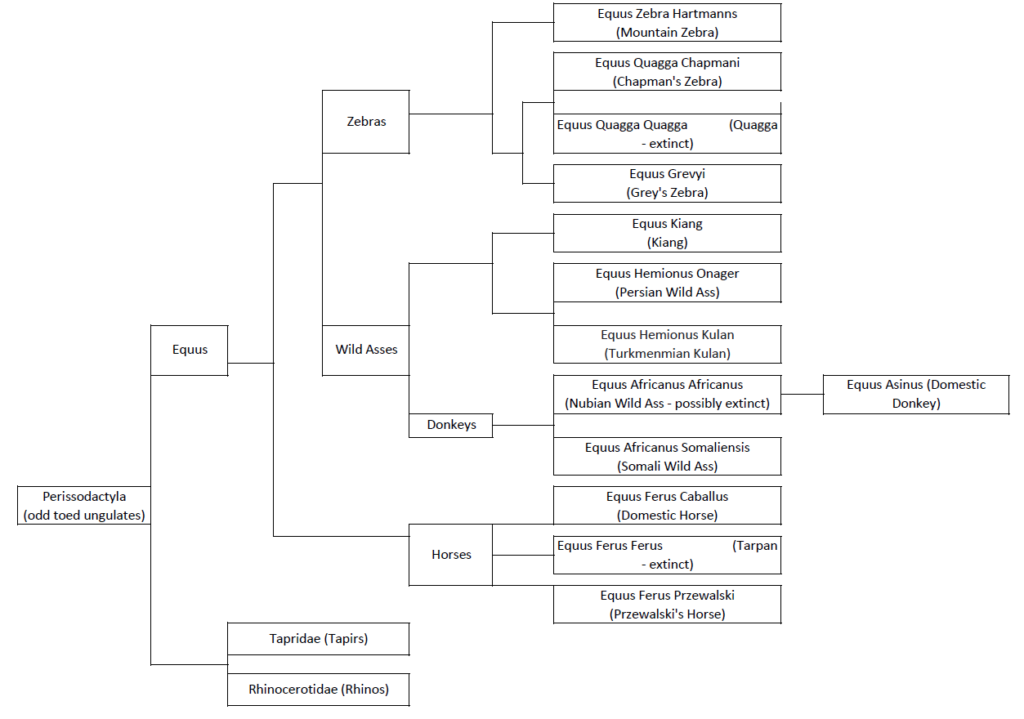

The Donkey, scientifically known as Equus asinus, is member of the Equidae family which also includes the horse (Equus ferus caballus). DNA research indicates that the E. asinus line separated from the caballus line around 3.4 – 3.9 million years ago. Donkeys were domesticated around 5,000 BCE, an event that revolutionised ancient societies and overland transport in African and Eurasian societies by advancing trade abilities. However, the actual origins of the domestic donkey are somewhat murky. For a long time, it was believed that the domestic donkey descended primarily from the Nubian Wild Ass (Equus africanus africanus), with some Asiatic donkey breeding also part of the mix. However, recent DNA analysis has indicated the likely ancestors were the Nubian Wild Ass and another subspecies separate from the modern Somalian subspecies. So, unlike horses which are a Eurasian plains animal, the donkey is a semi-desert animal from Africa.

The correct term for the donkey is ass, which is thought to originate from the Hebrew word Athon – which means female donkey. This word became the Greek asnos (ὄνον) and the Latin equivalent is asinus. More commonly in the English language they are known as donkey, a word with somewhat unclear origins. It could be that it comes from the English words dun, describing the colour of the animal, and ky meaning small. Or it could, perhaps, derive from the Flemish word donnekijn which means ‘small dun-coloured animal’. Certainly, the word goes back to the 13th Century, but the first written instance does not appear until 1785 in the ‘Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue’ by Francis Grose. In Central and Latin America, they are known as burro, which is of Spanish origin and is also the term for the free-roaming donkeys of the United States.

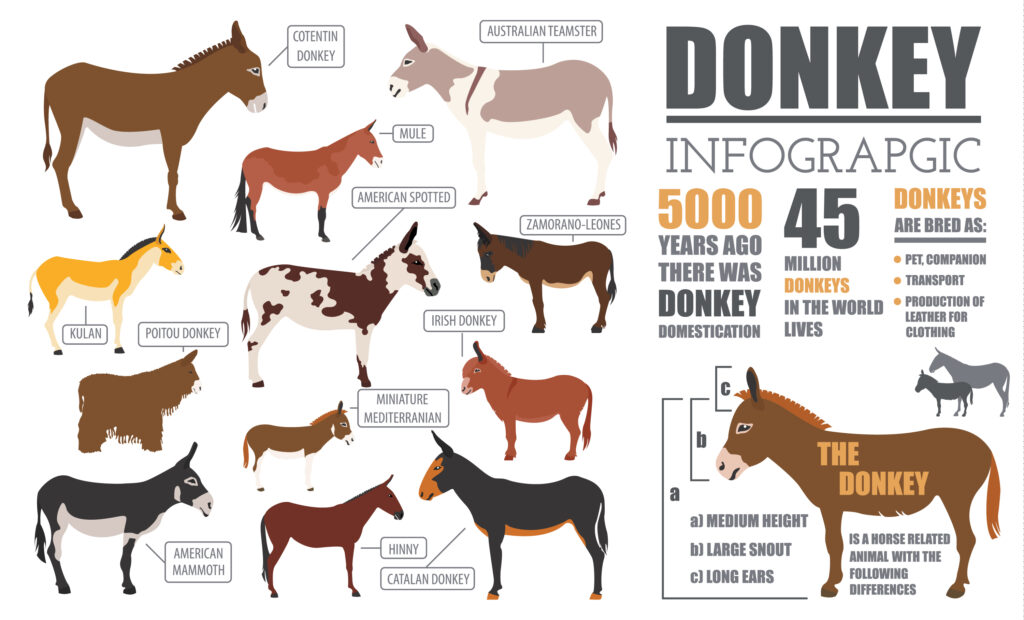

A male entire donkey is called a jack and a female donkey is called a jennet or jenny. A group of donkeys may be referred to as a drove, pace, or herd. Donkeys can be cross bred with horses and the cross between a jack and a mare is called a mule, whilst the cross between a jenny and a stallion is called a hinny. Mules and Hinnies are almost always sterile because their parents have a different numbers of chromosomes – donkeys have 62 and horses have 64. Donkeys have one of the longest gestation periods in the animal kingdom of between 11 – 14 months with usually a single foal. Donkeys live longer than horses; many of them live for more than 30 years.

Donkeys are more solitary than horses and do not form herds the same way; instead, they commonly live-in small groups or pairs. This is thought to be due to the sparser resources in their native territory, with the larger congregations formed for breeding when food is plentiful. To improve their chances of finding a mate, a donkey jack may defend a territory that holds a desired resource, such as a water source, that will attract the jennies. Jennies may also guard resources. This explains why donkeys may display territorial behaviour when living alongside other animals.

As mentioned above, donkeys are believed to have originated in the desert and, as a result are adapted to be more efficient at using feed and water than a horse. Like horses, donkeys graze on grass, but they can also browse on tougher stuff like shrubs and bark. This is possible because the bones of their skull are much larger than a similar sized pony, and they have a powerful jaw to grind tough plants and shrubs. They can browse on low nutritional forage for 14 – 18 hours a day and walk up to 20-30 km. It is important that domestic donkeys are not given too much rich feed, as it can cause them to become overweight and develop problems like laminitis. They are further adapted to a desert environment by having their nasal ducts not on the floor of the nasal cavity as it is in the horse but instead on the lateral to dorsolateral aspect of the nostril, near the mucocutaneous junction. This different placement reduces the likelihood of blockages from sand.

The call of a donkey is called a bray; it can last for 20 seconds, be heard up to 3 km away and is believed to be easier to hear across rough terrain. Jacks bray to affirm their status and all donkeys use it to attract a mate, when isolated from their friends or when looking forward to food. It is unusual among Equidae in that the noise is made both when the donkey breathes in, and when they breathe out. Each donkey’s bray sounds unique. The sound of a bray is quite different to that of a horse’s neigh and is often described as ‘hee haw’. The donkey’s distinct, large, slightly pointed ears help them hear noises from over a great distance and are also useful for dispersing heat.

The domestic donkey and several wild ass species have a dark streak at right angles to the shoulders and down the withers, which is described as a cross. Possibly these markings are vestiges of the all over stripes such as those possessed by the zebra. Christian legend says that the cross on the donkey’s back is because it was touched by the shadow of the cross. Similarly, all ass species can be seen to have transverse leg stripes though in some species they are faint and small in number.

There are some less obvious physical differences between the donkey and the horse aside from distinctive ears and the cross on their back. One of these is that fact that donkeys can do a ‘standing jump’. This interesting talent relates to the donkey’s ability to jump up to quite a substantial height from a standstill. They can do this because off different proportions and insertions of musculature that allows for a greater range of motion than the muscling in a horse. The angles of their joints also play a part in their ability to jump like this (it also explains why donkeys can kick backwards, forwards, and sideways). The donkey parent passes this unusual ability to their mule offspring. Standing jumping competitions are popular in the USA where the record mule jump was set in 1989 by Don Sam and his mule Sonny in Arkansas. Sonny jumped 72 inches (about 1.80 metres!!).

Their lower withers, straight back, and smooth slow paces also make them an excellent pack or draught animal. The donkey’s hooves are of a more open tubule structure than the horse, which enables any moisture in the environment to be drawn into the hoof; this can be a great benefit in the low rainfall areas where the wild donkey developed but can cause problems when domestic donkeys are kept in wet areas and their hooves become waterlogged. The donkey’s hoof wall has a steeper angle than a horse’s, and the frog is set further caudally.

Humans initially considered donkeys as prey. Cave paintings from 6,000 BC from Wadi Abu Wasil in Egypt show hunters and dogs pursuing donkeys that look like the Nubian Wild Ass. This changed when the donkey was domesticated. It was originally thought that that donkey domestication occurred in either Egypt or Mesopotamia, because the earliest evidence of donkey domestication was found in these locations: such as the ten articulated donkey skeletons found in tombs at Abydos in Egypt date from around 3000 BC, or the donkey skeletons found by Sir Flinders Petrie in a tomb a Tarkhan, Egypt and dating from circa 2850 BC. But there are also those who believe that domestication could have originated in North-East Africa.

The domestication of the donkey was important because it transformed early pastoral communities. Using donkeys enabled them to move loads further, faster and with more frequency. It also allowed for large-scale food redistribution and the expansion over overland trade networks. The reason why the donkey was first domesticated may never be known, nor will the exact length of time it took, but since it pre-dates the wheel and riding it is likely they were initially used for pack carrying.

Although they are considered especially useful and revered by some cultures, they are also often described as stupid or clumsy. They are frequently regarded as substandard to the horse. They have a reputation for being stubborn, but what they are is stoic and in possession of a greater sense of self-preservation than horses. They are also often judged using the pain behavioural scales of the horse even though they are distinctly different in temperament and biology (for instance, they have different temperatures, pulse, and respiration rates than horses). They indicate reluctance with different body language than a horse or pony, with the actual cause more likely to be fear, pain, lack of motivation or confusion over directions given as opposed to stubbornness. Both donkeys and horses are prey animals that exhibit the ‘fight or flight’ response. As donkeys do not form large herds as horses do, instead living on their own or with their foals, fleeing is often not the best option and so they are more apt to engage their fight response. It is awfully hard to make a donkey do something that it considers dangerous; however, they can become very willing partners once you have earned their confidence. They also do not have the same tendency to spook as horses, which can be great!

Although they may live a solitary existence in the wild, donkeys are naturally gregarious and thrive when provided with the company of their own species. They develop strong bonds with other donkeys and will tend to choose to socialise with other donkeys if placed with a choice of donkeys, ponies, or mules. If a donkey is separated from a bonded companion, they may get so distressed that they develop the possibly fatal metabolic condition hyperlipemia.

These days there are around 40 million donkeys in the world, made up of 97 different breeds. Of these we currently have four present in Australia – the Mediterranean Miniature, The English Irish, The Australian Teamster, and the American Mammoth Jackstock. These range in size from 36” (8 hh) in height, to 64” (16hh).